The Hamilton Electric

In the 1961 movie, "Blue Hawaii," Elvis Presley appears in several scenes wearing a Hamilton Electric Ventura, a modernistic, boomerang-shaped watch introduced four years earlier. In the 1961 movie, "Blue Hawaii," Elvis Presley appears in several scenes wearing a Hamilton Electric Ventura, a modernistic, boomerang-shaped watch introduced four years earlier.

It was a funny coincidence that the singer who electrified the pop music world with his twangy Cadillac-finned guitar should sport a finned rendition of the watch that had electrified timekeeping. For the Hamilton Electric marked a horological turning point. As the first battery-powered watch, it sparked the revolution that would oust the mechanical watch and replace it with quartz technology. Unfortunately for Hamilton, its new Electric, despite its innovative movement, was as much steppingstone as milestone. Even as teeny boppers were getting their first glimpse of "Blue Hawaii," the Electric had become a burned-out has-been, a victim of bad decisions and worse luck. The original model, the "500," was a frustrating, problem-laden five years in the works. But even half a decade wasn't long enough, as it turned out. Hamilton rushed the watch to market prematurely because it knew Elgin was working on a similar one. The problem with the 500 lay chiefly in its electrical contact system, which wore out quickly and was very difficult to repair. The 500s came back into stores almost quickly as they went out. Hamilton introduced an improved version of the watch in 1961. But it was too late. The year before, Bulova had upstaged Hamilton with the launch of its extraordinarily successful Accutron tuning fork watch, which was more accurate and reliable than the Electric. Ironically, the victory could have been Hamilton's. When the company was designing the Electric watch, it considered using a tuning fork oscillator, which is what made the Accurton so accurate. Ultimately, though, Hamilton had decided to stick with a traditional balance, like that used in mechanical watches. The company also considered using a transistor, which would have eliminated the electrical-contact problem, but it rejected that idea, too. The Hamilton Electric still has many admirers among collectors - those who love its quaint Eisenhower-era styling and equally quaint technology, those for whom its story of worry and woe make it all the more valuable.

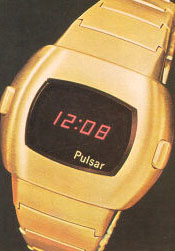

It was an unpromising debut. But when the watch finally appeared in stores two years later, its energy-depletion problem solved, it was a runaway success - despite its $2100 price. More importantly, it was a landmark. It was the world's first digital watch; the world's first purely electronic one. Unlike the analog quartz watch that preceeded it, the digital quartz watch had solid-state construction, i.e., it had no moving parts at all. The Pulsar incorporated a type of display called an LED (light emitting diode) which lit up when the wearer pushed a button and remained illuminated for about one second. The push-button feature was designed to conserve battery power, of which the light-up numbers consumed vast quantities. The watch attracted a flock of famous admirers: Presidents Nixon and Ford owned Pulsars; so did the Shah of Iran, Haile Selassie and many other public figures. Bergey remembers visiting Tiffany's New York store, the biggest seller of the watch, to see the Pulsar phenomenon first-hand. The Pulsar showcase was a hub of activity, he recalls. Customers would sidle up to the counter, pluck down a wad of money and point to the Pulsar of their choice as casually as if they were buying a jelly doughnut. The fever didn't last. Within five years, competition was hurting the brand badly. Plus, consumers had fallen in love with a new type of digital, one with a continuous time display: the LCD (liquid crystal display). The Pulsar divisio was sold to a U.S. firm called Rhapsody Inc., then to Seiko. In 1979, Seiko launched its first watch under the Pulsar label. It was an analog, not a digital. Pulsar was out of the digital business but an army of other companies had come in. By 1980, one in every three watches sold in this country was a digital watch. At century's end, watch companies are making 350 million digital watches a year. |

John Bergey, former president of Hamilton's Pulsar division, still laughs when he remembers the 1970 press conference announcing the new Hamilton Pulsar watch. He and his Hamilton colleagues had to keep slipping out of reporters' sight to change the watch's batteries. The watch had a nifty new type of display that showed the time not with hands and a dial but with bright red numerals. The light-up display was something to see. But you couldn't see it for long, because it drained the watch's power dry in just a few minutes.

John Bergey, former president of Hamilton's Pulsar division, still laughs when he remembers the 1970 press conference announcing the new Hamilton Pulsar watch. He and his Hamilton colleagues had to keep slipping out of reporters' sight to change the watch's batteries. The watch had a nifty new type of display that showed the time not with hands and a dial but with bright red numerals. The light-up display was something to see. But you couldn't see it for long, because it drained the watch's power dry in just a few minutes.